Advent of Code won't teach you a programming language

Every year, programmers around the globe rejoice as December approaches. Precisely 24 days before Christmas, they are about to discover what kind of twisted puzzles the man himself has devised for them this season. “The man” here is Eric Wastl, creator of the beloved Advent of Code.

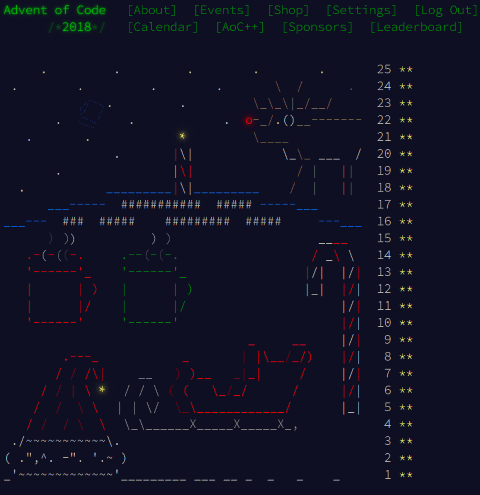

For those unfamiliar with it, Advent of Code is an advent calendar of programming puzzles which can be solved in any programming language. Each day between December 1 and December 25, a new puzzle automatically unlocks at midnight EST, blend into a storyline about Santa, reindeer and elves. The fastest programmers to solve it are recorded into a global leaderboard, which adds a spicy edge to the game for those seeking competition.

These puzzles are well crafted and it shows; a considerable amount of work is being put into them, beginning several months before the event. If you are curious about the details, do check the talk Advent of Code: Behind the Scenes on YouTube.

A lot of people seize this opportunity for learning a new programming language instead of competing. Others focus less on the language itself, and more on finding creative approaches to finding particular solutions. As a wrote above, Advent of Code can be solved in any programming language by design, which makes them a great fit for this endeavor.

I recently started catching up on the 2023 edition (about time) after the topic came up in a discussion with a friend. I too picked a language which felt foreign to me for solving the puzzles this year. A few days into the season and based on my experience from previous seasons, something occurred to me: Advent of Code helps me sharpen my problem-solving skills, but doesn’t make me better at writing idiomatic code in my chosen programming language.

Generic problems require generic approaches

Let me get into the nuances hidden behind my bold post title.

Whoever has ever taken part in the Advent of Code will presumably agree that its puzzles have a few recurring patterns: it generally starts with some large(-ish) input data that needs to be parsed line by line, then either reduced on the fly or collected into the appropriate data structure for further computation. In the end, the expected answer is always an integer or some short sequence of alphanumerical characters.

The fact that the problems presented by Advent of Code do not favor one specific programming paradigm is part of what makes them so appealing. This type of challenge is excellent for practicing the usage of data structures, adopting a performance-oriented mindset, and identifying common algorithms. It is also a compelling excuse for putting the syntax and core constructs of a language to the test.

However, when I personally jump into a concrete software project—no matter its size—my primary concerns aren’t the aforementioned aspects. Instead, I find myself needing to understand traits of the language which are unique to that language: how abstractions can be created and organized into modules, the dynamic of cross-module interactions, how to interact with the user and/or external systems, how to handle errors, how to approach memory management and safety, how to orchestrate concurrent tasks, etc.

None of this know-how is being leveraged while solving Advent of Code1. This is in no way a criticism, just my observation of what these exercises train for, and conversely what they don’t. I enjoy solving these programming puzzles as much as the next computer geek, but it feels fair to say that their outcome is more actionable for preparing for job interviews than it is for building tangible projects.

In essence, picking a foreign language for solving Advent of Code is not an act of learning how to engineer better software in that language, but rather an act of practicing coding while challenging oneself and having fun doing it.

Getting proficient with the language

I couldn’t end this post without sharing my perspectives on how to become actually proficient with a new programming language.

You may have read this over and over again, and that’s because it is true: instead of completing 100 coding puzzles, pick a reasonably small project that you have a genuine interest in, break it down into small units that you can commit yourself to completing based on the time you have at hand, and get your wheels spinning. It does not matter how long it takes, it does not even matter whether you finish all the units that you had originally identified2. What matters ultimately is to get comfortable writing more useless software; not “useless” in the sense of without any purpose, but without expectation of it being ever run by someone else than yourself. The experience you will gain engaging in solving concrete problems in that new language will be an order of magnitude more rewarding than puzzle-solving on the long run. It’s what we do in our daily jobs, after all.

How to decide upon an interesting project to tackle is fairly subjective, and depends both on personal aspirations and affinities. Here are a few propositions:

-

One possibility is to pick something you are already familiar with, for instance something you were exposed to at work, and try building something similar on your own terms, taking into accounts the idioms, strengths and constraints of the new language.

-

Another one is to search the Internet for ideas. This can yield interesting suggestions including challenging ones, but finding something relevant to you can require quite a few search refinements. I recently stumbled upon the Coding Challenges newsletter by John Crickett, and have been impressed by the breadth of the projects contained in its archive.

-

Finally if there is something you feel particularly attracted to—like a game—but aren’t sure whether it will bring you objective value, just go for it. There is value to be found in any software project along the way.

In the end, nothing cultivates motivation better than curiosity.